Patients who suffer an intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) face an increased risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) during their hospitalization. AKI can lead to sudden kidney failure, kidney damage or even death.

Researchers from the University of Missouri School of Medicine and MU Health Care have determined which ICH patients are at the highest risk for this kidney injury so doctors can take precautions to prevent it. They also examined how the commonly-used blood pressure lowering drug nicardipine contributes to AKI.

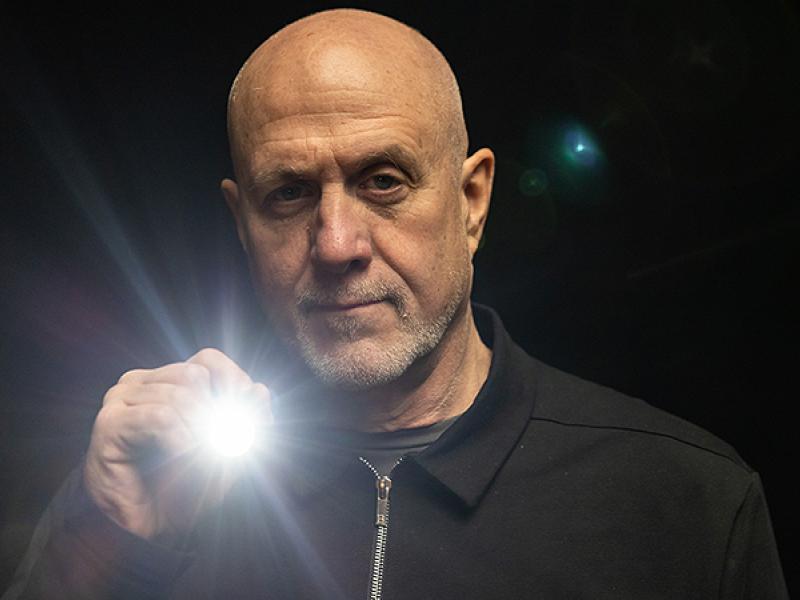

“Over the past five years, clinicians have been concerned about AKI as they see patients who present with ICH, then develop kidney failure and require dialysis,” said lead researcher Adnan I. Qureshi, MD, a professor of clinical neurology at the MU School of Medicine. “What we need is a more global body approach to improve the outcome of patients with ICH, rather than just focusing on the brain.”

Qureshi’s team analyzed data from a multicenter trial in which 1,000 ICH patients with systolic blood pressure above 180 to either intensive (110-139 mm Hg) blood pressure reduction or standard (140-179 mm Hg) reduction within 4.5 hours after symptoms started. Researchers identified AKI by taking creatinine blood samples — which show how well the kidneys are functioning — from each patient for three days. They found 15% of all patients developed AKI, higher doses of nicardipine were linked to an increased risk for AKI, and a higher baseline serum creatinine level was associated with a greater risk for AKI. In addition, those with AKI were nearly three times more likely to die within three months of diagnosis.

“Even the initial set of labs seem to have predictive value in who will develop AKI, and I think this study highlights the values doctors can use to actually determine who may be at risk,” Qureshi said. “What we thought was an isolated brain disease, is not necessarily the case.”

Qureshi believes the next step in preventing AKI after ICH is to use serum creatinine and other markers to identify high-risk patients, then use proactive measures to carefully manage intravenous fluids and avoid medications that are more likely to cause or worsen AKI.

In addition to Qureshi, the study authors include fellow MU School of Medicine collaborators Wei Huang, MA and Iryna Lobanova, MD, research specialists in the Department of Neurology; and Kunal Malhotra, MD, a former associate professor of clinical medicine.

The study, “Systolic Blood Pressure Reduction and Acute Kidney Injury in Intracerebral Hemorrhage,” was recently published by the journal Stroke. Research reported in this publication was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center. The contents of this publication do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.