Asthma is one of the most common chronic conditions in the United States, affecting about 1 in 12 people. It’s likely caused by hyper-responsive airways that become inflamed and, as a result, restrict breathing.

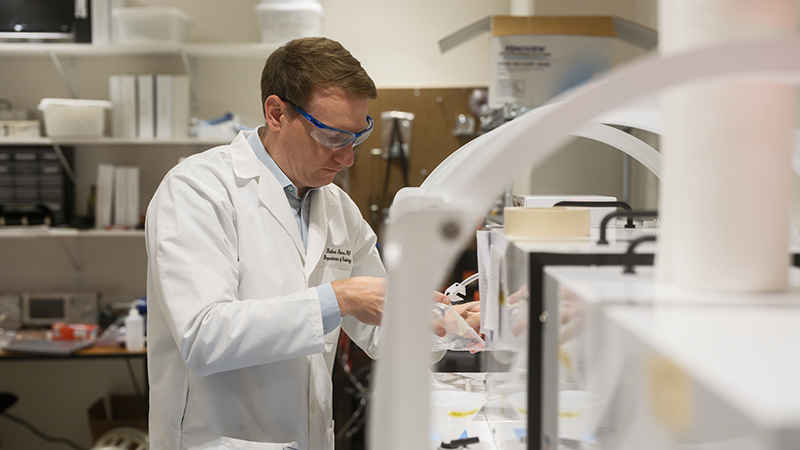

Now, a University of Missouri School of Medicine researcher has received a $1.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to investigate whether this same hyper-responsiveness also happens in the lung’s blood vessels, or its vasculature.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines rely on the water in human bodies to create clear scans, but this becomes an issue when trying to scan the lungs for asthma, since they’re full of air and not water. But the machines can be programmed to detect another element, and for respiratory illnesses, that element is xenon gas.

“This is an old hypothesis in asthma studies, but historically, there wasn’t a viable way to measure regional hyper-responsive blood vessels or to see this on a scan,” said Robert Thomen, the grant recipient. “A hyperpolarized xenon gas MRI may change that.”

When inhaled, non-reactive xenon gas serves as a bright, trackable signal that shows the flow of breathing into the lung tissue and bloodstream. By following its path, researchers can observe how well different regions of the lung exchange gases and identify signs of abnormal vascular responses that may contribute to asthma.

“It gives doctors a better understanding of how the lungs function and helps with creating a better, tailored treatment plan for the patient,” Thomen said.

The grant will fund the scans of healthy patients and patients with varying severities of asthma. If Thomen and his team can produce clear images of asthmatic breathing and gas exchange, it can help develop new, targeted asthma treatments.

Robert Thomen, PhD is an associate professor of radiology and bioengineering at the Mizzou School of Medicine and the College of Engineering, respectively. He is also a NextGen Precision Health Investigator. The NIH grant will provide $1.8 million over four years.