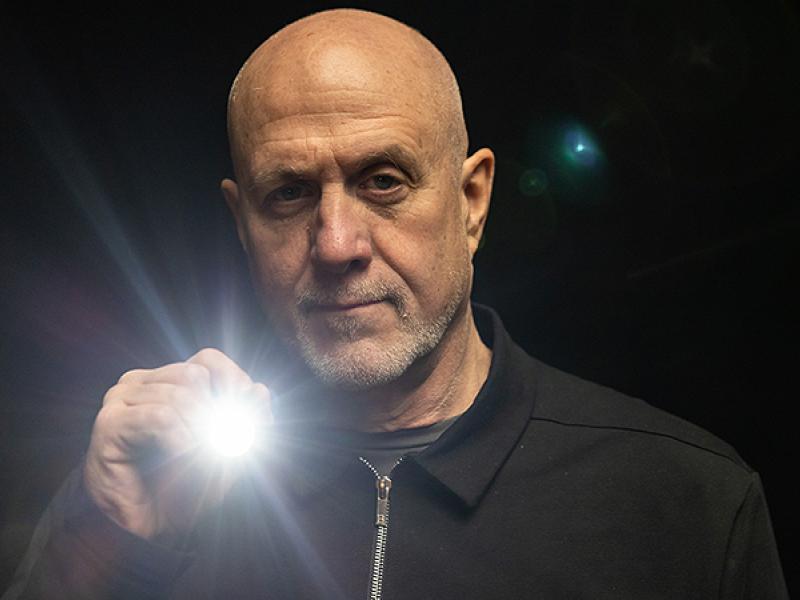

In the spring of 2020, Marc Johnson, PhD, received a fateful email from the state Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS). It asked if someone at the University of Missouri could lead a project that would test wastewater samples from around the state to track COVID-19 infection levels. Johnson, a virologist whose previous research was geared toward potential treatments for HIV, didn’t know anything about testing wastewater.

But, given the circumstances, he volunteered for duty.

“If the state was coming to the university to ask us for help during a pandemic, I didn’t think we should say no,” said Johnson, a professor in the Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology.

More than two years later, Missouri’s Coronavirus Sewershed Surveillance Project has become a national model for providing the most comprehensive, transparent and timely snapshots of the state’s COVID-19 situation. The partnership between DHSS, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and MU has generated information that helps local public health officials — or anyone else — plan for the ebbs and flows of the pandemic.

Ultimately, the project also could help answer the big question that has captured Johnson’s scientific curiosity: Where are the COVID-19 variants coming from? If that question can be answered, it will be easier to contain new variants before they spread widely.

“This is the most exciting thing I’ve ever done,” Johnson said. “Tracking these variants has come to control my life. I spend all my time looking for these oddballs.”

Team Effort

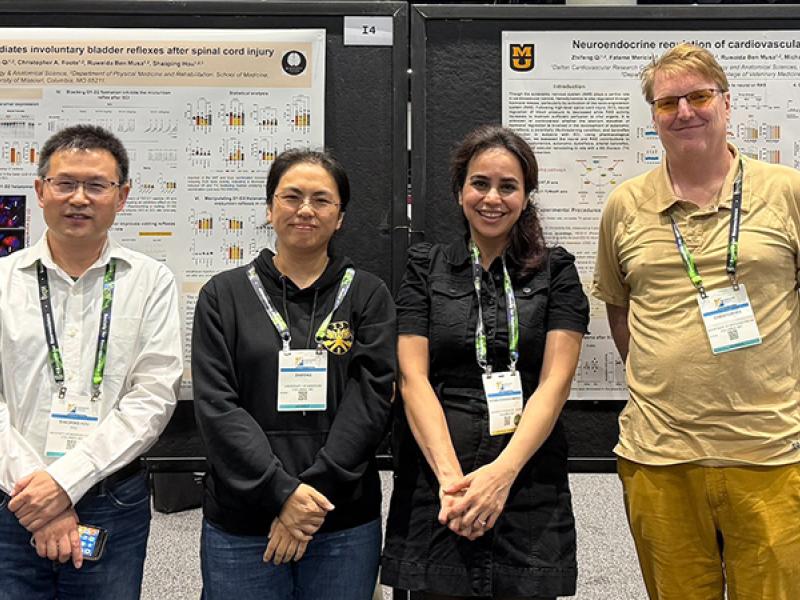

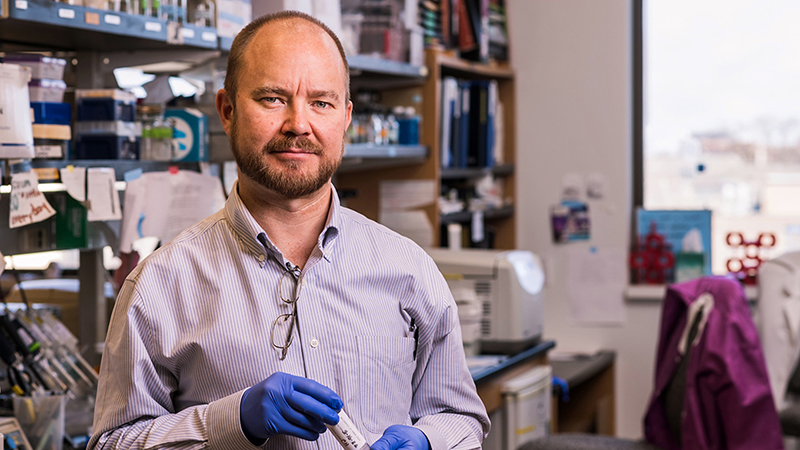

To get the project off the ground in May 2020, Johnson needed to find a partner with expertise in wastewater testing. He found one in chemist Chung-Ho Lin, PhD, from the MU College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. Lin studies bioremediation — using living organisms to clean up environmental messes — and he had experience analyzing levels of contaminants in wastewater.

Lin knew sewage was a mostly untapped resource for determining the health of a community by providing evidence of everything from the level of prescription and recreational drug use to the presence of pathogens such as COVID-19.

“Wastewater never lies,” Lin said. “Give us 15 milliliters of water, and we can tell you a lot of stories.”

Johnson and Lin work well together, although they are rarely together. Their labs are in different buildings, and they didn’t physically meet until three months into the project … and only then because they were being interviewed for a TV news story. Their preferred schedules — Johnson is a morning person and Lin a night owl — create a natural workflow that allows them to test and analyze samples throughout the course of a day.

Each week, samples are collected from more than 100 wastewater treatment plants, sewershed access points, prisons and psychiatric institutions across Missouri and delivered to Johnson’s laboratory in the Bond Life Sciences Building. Johnson’s team spins the samples in centrifuges to extract the RNA and then stores them in freezers until they go to Lin’s lab at the Anheuser-Busch Natural Resources Building. Lin’s team uses qPCR machines to amplify the RNA, detect COVID-19 and quantify the amount present. All that information is recorded and shared with DHSS, which regularly updates the project’s website.

Lin, who served in the army in his native Taiwan, compared the wastewater surveillance project to a military operation because of the finely tuned cooperation and coordination between government agencies and the state’s flagship university.

“For scientists, this is a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” Lin said. “We get to come in and prove that higher education and science do make a positive impact in the community. I was able to witness that from scratch.”

The cooperation between DHSS and DNR and their unwavering support of Johnson and Lin helped the Missouri project adapt as the virus evolved. By the end of 2020, variant strains of COVID-19 started to emerge. By February 2021, Johnson had developed a method for sequencing the samples to determine not just the level of COVID-19 in communities but the specific strains of the virus present.

“Once we started sequencing, that was right in my wheelhouse,” Johnson said. “Missouri has the most advanced sequencing system in the country, if not the world, right now. A lot of it is because we have this partnership with the state that’s funding the research, but it’s being driven by academics. So Chung-Ho and I are constantly saying, ‘Let’s try something else and keep improving it.’”

Sewage Sleuths

Mutations can occur all over the genome of the COVID-19 virus. While it is possible to sequence and map an entire COVID-19 genome from an individual positive PCR test, it is impractical to do that for a sample of viruses from the wastewater of multiple living things. Johnson compared it to trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle from a bag containing the pieces of 20 puzzles.

His solution was to sequence only one small region of the virus’ spike protein, which is where most of the mutations occur as the virus is adapting to a new host. Johnson takes samples of RNA from the spike protein region and runs them through a genome sequencing machine. It determines the order of the four bases — guanine (G), cytosine (C), adenine (A) and thymine (T) — and spits out a text string with a combination of those letters.

“It’s about 550 letters in a row, and we know what letters are there, what order they’re in and which letters should go with the same letters in the same sentence,” Johnson said. “No one else was doing it this way. Now, we have this sequence, so if anything new appears, we know it. We read the sequence and know, ‘These mutations have not been seen before together.’”

In May 2021, Johnson first noticed a sample with evidence of the delta variant in one of Branson’s two sewersheds. The next week, delta had taken over the first sewershed and was present in the second. The following week, it was erupting all over the Missouri map like popcorn.

“I think a lot of people were taking trips to Branson and bringing a present home,” Johnson said.

But for every delta or omicron variant that sweeps the world, there is another oddball whose sequence looks menacing on a computer screen but quickly fizzles. Understanding the origin story of variants has become something close to an obsession for Johnson. He keeps track of where new variants are popping up and collaborates with other COVID-19 detectives around the world who are trying to identify emerging mutants and trace them backward from the sewershed to an area as close as possible to the source.

“If it turns out the variant is coming from a person, it’s in everyone’s best interest — both the person and society in general — that that person is isolated and given any medication they can to clear that infection,” Johnson said. “If they can clear the infection, the threat to the public is gone. If it’s coming from an animal reservoir, it at least gives us a clue of where we need to pay attention. Maybe it turns out you would have to be more cautious around certain animals. If nothing else, it would tell you where you can do surveillance for potential new variants. Once we find the first one, everything is going to fall like dominoes and it might get boring, but for now, I would do this work for free.”